Longevity and Morbidity in the Irish Wolfhound in the United States - 1966 to 1986

Updated Introduction (2003)

It never occurred to me to ask, when we began looking for our first dog in 1968, how long I might expect my dog to live. All I knew was I wanted an Irish Wolfhound and I just presumed that all dogs had about the same lifespan. When our first wolfhound died very young of torsion, I began to understand this sole disadvantage of life with wolfhounds and also began to ask questions. I received many answers; the problem was, all of the answers were different, because everyone was guessing.

In 1986 I interviewed a veterinary oncologist at the University of Illinois for an article I was writing on bone cancer for the Irish Wolfhound Quarterly, for which I was then a regular columnist. To explain my interest in the subject, I mentioned that it was one of the major killers of Irish Wolfhounds. “Not even close,” he said. “Trauma is the number one killer of your breed.”

I knew that could not be the case, but who was I to argue with a top veterinary researcher at a major university? I, too, had only been guessing, but all of my data was anecdotal and he referred to the results of real, scientific inquiry. As it turned out, the data which he used came from major emergency clinics throughout the United States and so the numbers were naturally skewed towards trauma.

But that frustration led to this study. I just wanted to know the truth, or at least as close to the truth as I could get. I wanted my project to be as scientifically irrefutable as possible and to that end, I enlisted the help of epidemiologists, population geneticists, statisticians and medical researchers in two major teaching hospitals (human) in St. Louis, Missouri. Additionally, I spoke with and was helped by several researchers and clinicians at both the University of Illinois and the University of Missouri Veterinary Schools.

I was persuaded to undertake this study because I was suspicious of guesswork and so I am especially careful not to engage in it myself. However, I am asked frequently how I think the results would differ if I were to do the study today. The only answer I can honestly give is that I think, but cannot prove, that we would see a much higher incidence of death due to heart disease. I say that not because I think we have more wolfhounds suffering from heart disease today, because I truly do not know if that is the case. But we are certainly testing our dogs more today, using more sophisticated diagnostic tools with the testing being conducted by more experienced clinicians.

Gretchen Bernardi

May 27, 2003

Introduction (1998)

Irish Wolfhounds in the United States from 1966 to 1986 lived to a mean age of 6.47 and they died most frequently of bone cancer. These facts are the result of a privately funded study conducted under the auspices of the Irish Wolfhound Club of America, Inc.

Methodology

This is a retrospective study examining data about previous conditions and is concerned with Irish Wolfhounds that died over a 20-year period in the past. By definition, a retrospective study depends on the respondents' memory and knowledge and this dependency is a great disadvantage in human epidemiology, since hundreds of events and incidents must be recalled over a long period of time--the human life span. Since the life span of the Irish Wolfhound is much shorter and the medical activity that occurs within that period generally less complex, the disadvantages are perhaps not as great as they might be in human studies.

When a study is undertaken to determine any condition of a segment of population, whether it is plant or mineral, dog or cat, human or non-human, it is necessary to examine data from a sample of that population. The researchers are required to choose a segment, or sample, that is as unbiased and as satisfactory as possible and to use methods for selecting a sample that will achieve that end. Had I had at my disposal the records of registration from the American Kennel Club of all Irish Wolfhounds born between 1960 and 1986, my problem would have been to take from that population a randomly determined sample to produce a list of owners to whom we would send the questionnaire. But those records were not at my disposal, due to American Kennel Club policy.

I therefore took as my sample the only available list of Irish Wolfhound owners in the United States, which was the combination of members of the Irish Wolfhound Club of America (the parent club) and members of all regional Irish Wolfhound clubs, whether or not they were sanctioned by the American Kennel Club. A letter was sent to the secretaries of these regional clubs describing the nature of the study and requesting their complete membership lists; all but one did so. I combined those with the parent club membership lists (both active and associate), eliminated the duplicates and arrived at a sample list of 1,005 members, to whom I sent the questionnaire accompanied by an explanatory letter.

I originally feared that we would reach only the "show" segment of wolfhound owners and that the level of attention and veterinary care provided by these owners might be different than that of the general population, although I had no quantitative findings to support such an assumption. This has not proven to be the case; in fact, only a small percentage of the dogs in this study held titles (conformation, obedience or coursing). Combining this fact with personal observations in analyzing the data, I believe the sample of this study is representative of the Irish Wolfhound population in the United States.

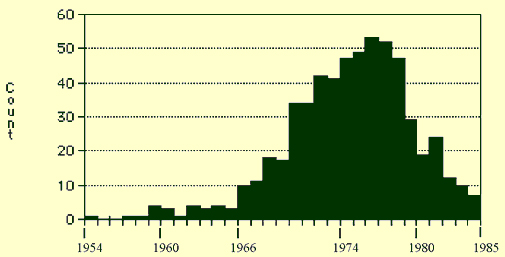

An interesting but disappointing note on the sample: very few dogs that were born before 1965 are represented in this study. The earliest birth date is 1954, but there are only a few dogs in the study born between 1954 and 1966, and there is a dramatic increase at about that time (see Table 1). To be sure, the Irish Wolfhound population in this country underwent noticeable growth at about that time, but there is also a "life-span" of dog ownership in general and this likewise applies to Irish Wolfhound ownership. Many people who had dogs that would have died in the early years of the study period, 1967 to 1970, no longer own wolfhounds and therefore no longer have club affiliations. Because of that, they did not appear on any of the membership lists. Another contributing factor is that many owners of long standing did not reply to the survey.

Table 1 - Year of Birth

Does the absence of these owners' data make a notable difference in the outcome of this study? Before the effect of refusals on any epidemiological project can be estimated, it must be determined why the surveys were not returned. There can be several reasons and two of the most common are:

- Difficulty of the questionnaire itself.

- Reluctance to answer certain questions.

Considerable care was taken to arrive at a questionnaire that was as short and as simple as possible, still providing the necessary data. Furthermore, the option of responding anonymously would have eliminated the second consideration if the owner felt any threat to his reputation or to that of a certain bloodline. Additionally, the exact name of the dog was not required in the study. But at the very least, a form had to be filled out for each dog that died over a 20 year period and that could have been intimidating to owners facing 30 or 40 questionnaires. Realizing this, I am especially grateful to those who made the effort to do so.

In the field of epidemiology it is widely believed that age is a factor in whether or not a person will respond to a survey on any subject. Several studies have shown that after the age of 35-40, there is a marked and steady drop in participation in questionnaire-based surveys and the reasons are many and complex. But the age of those owners who would have had dogs in the early period of this study may have been a factor in the small sampling from that time frame.

Naturally, some of the categories were more difficult than others for the respondents. We can presume the sex of the dog is correct when given in almost all of the cases, and very few were unclear on the dates of birth and death. As a matter of fact, the vast majority of owners knew these dates precisely, including day of the month. But the cause of death is a different issue altogether. From the planning stage, I had anticipated a problem with this category for several reasons unrelated to lack of memory on the respondents' part:

- Reluctance on the owners' part to allow autopsies.

- Unreliability of autopsy findings when they are performed.

- The tendency of the attending veterinarian to offer a reasonable guess in the case of a sudden, unexplained death and the tendency of the owner to take that guess as a definitive pronouncement.

- The reluctance of most owners to spend the time and money for definitive diagnostic tests, particularly in the case of incurable diseases, and their further reluctance to expose a pet to invasive diagnostic procedures when the probable outcome is a terminal disease.

- The tendency to be more specific than the actual data will scientifically permit. For example, if the cause of death is listed as a disease that can only be accurately determined by post-mortem histological examination and the respondent stated that there was no autopsy performed, that data becomes immediately invalid and the cause of death in that specific wolfhound automatically became "unknown."

I encountered all of these problems and more. One problem was the subject of cardiomyopathy, which does not appear in veterinary literature until the latter part of the study period, although we can assume that this form of cardiovascular disease existed, albeit undiagnosed and/or differently named. Another problem was the diagnosis of the specific type of cancer presumed to have caused the dog's death. Some of these are very clear cut, such as osteogenic sarcoma. But in the case of lung cancer, for instance, it is difficult to determine if the lesion in the lung was a primary or a metastatic tumor.

The only practical solution was to make some compromises in the degree to which the cause of death can be accurate. To say that the cause of death was cardiovascular disease or cancer will have to be adequate in this study, except when the survey was returned accompanied by a pathologist's or autopsy report as several were.

I was encouraged to learn that this is not a problem confined to this study or to veterinary as opposed to medical studies in general. Even though human death statistics are generally complete in most areas of the United States, determining the cause of death from such records as death certificates has always remained unreliable. For many years cause was determined by set rules published in the International Classification of Causes of Death and the Manual of Joint Causes of Death.1 But this was changed in 1948 to accept the cause chosen by the attending physician and the authority became the Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death.

But cause of human death is still far from accurate. Herbert L. Lombard and Elliott P. Joslin, in an attempt to determine the degree of accuracy of human death certificates, traced health and death records of patients from the Joslin Clinic in Boston.2,3 In a group of over 2,000 diabetic patients, diabetes was not even mentioned on 23% to 25% of the death certificates. And other diseases, particularly cancer, pose even larger problems due to the question of primary versus metastatic disease.

In 1966, Heasman and Lipworth undertook a study to determine the accuracy of death certificates in the United Kingdom.4 After analyzing 9,501 autopsies in selected hospitals, they revealed that clinical and autopsy diagnoses agreed in only 45% of the deaths. However, an interesting phenomenon comes to our aid-errors in classification occur in two directions. Some deaths from a particular cause are assigned wrongly to the other causes, while deaths from the other ones may be assigned wrongly to that cause. In Data Handling in Epidemiology, W.W. Holland reassures the investigator that "individual errors cancel each other out, at least partially, resulting in smaller net aggregate errors. In this sense the reliability of statistics on causes of death is higher than the individual accuracy would indicate." He further states that in most studies on the accuracy of death certificate diagnosis, "in spite of the relatively large individual disagreement between original and final diagnoses, the total numbers of deaths assigned to a cause before and after review were frequently similar because of compensating differences...."5

In the United States and in most countries of the world, statistics on the cause of death are compiled by coding the underlying cause of death, despite the fact that the usefulness of this practice has been challenged. As far as I can determine, there is no uniform coding method adhered to by veterinary clinicians. This presents a problem in a study such as this, but perhaps not as major as first thought. Most epidemiologists agree that the "underlying cause of death" approach breaks down severely when dealing with deaths occurring at an advanced age and involving several serious pathological conditions. Because of their short life-span, Irish Wolfhound death statistics do not often confront us with this problem. Although some dogs were reported to have died in their sleep at age 10 or 11, these were the minority. In fact, a significant number of the wolfhounds who died past the age of ten were euthanized because of age-related problems, primarily arthritis or spondylitis (inflammation of the intervertebral articulations).

Note: There was an error in the questionnaire which did not become evident until analysis of data actually began. We failed to ask if the dog had died or had it been euthanized. This was simply an oversight on my part which was not caught by my consultant, who is an epidemiologist in human research to whom the subject would obviously not be relevant. Many owners either made a definite statement on this subject or answered the question in the course of explanation, but it should have been a specific question.

So, this study which strives to determine to what age Irish Wolfhounds live and of what they die can be expected to be only slightly less accurate than those studies seeking to answer similar questions about the human population.

Age at Time of Death

After removing from the returned questionnaires those dogs who were ineligible for the study (reasons: still alive, death did not occur within the time of the study, information incomplete or unclear), I arrived at 582 individual dogs, sent in by 222 owners (over 100 additional people sent replies that they did not have dogs that died within the study period, to assure me that they had received the letter and were not simply ignoring it). Of these 582 dogs, 291 were male, 274 were female and the sex of 17 was unspecified by the owners. Only a very small percentage of the animals in the study had been spayed or neutered and the numbers were somewhat higher in the latter years of the study period, presumably due to increased safety of general anesthesia, lessening owners' reluctance to have the surgery performed.

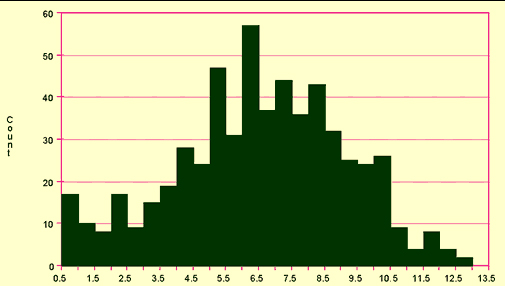

The youngest Irish Wolfhound in the study was .5 years, the oldest 13.5 years and the mean age at time of death for dogs of both sexes was 6.47 years (see Tables 2a and 2b). In males, the youngest reported age at death was .5 years, the oldest 13.5 years and the mean age for males at time of death was 6 years. In females, the youngest reported death was at .58 years, the oldest at 12.53 years and the mean age for females was 6.55. It has been generally accepted that female Irish Wolfhounds live longer than males, but I believe that the difference was presumed to be greater than .55 years, just a little over six months.

| Data File: IW Morbidity Variable: Age at Death |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum: | 0.500 | Maximum: | 13.500 |

| Range: | 13.000 | Median: | 6.580 |

| Mean: | 6.471 | Standard Error: | 0.109 |

Table 2b - Age at Death

Cancer

Cancer was the overwhelming killer of Irish Wolfhounds in the United States in the time period under consideration and almost as many dogs died of all forms of cancer as from the next three principal causes of death. Osteogenic sarcoma (bone cancer) was likewise overwhelming as the most prevalent type of cancer. Of the 582 dogs in the study, 197 (or 33.9%) died of some form of cancer. Osteogenic sarcoma accounted for 122 of those deaths, which is 61.9% of the cancer deaths and 21% of all deaths. No other disease or cause of death came close to that figure. It is probably true that most people with lengthy associations with the breed have felt that this disease was very prevalent, but few would have guessed the enormity of the problem as shown in this study. Additionally, it would seem that misdiagnosis or masking of this particular disorder would be very unusual, since its symptoms are so characteristic, unmistakable and not likely to be overlooked.

Veterinary literature indicates that osteogenic sarcoma is more prevalent in dogs than in bitches, but this was not true of these Irish Wolfhounds. Dogs comprised 49.2% of the deaths from this disease and bitches comprised 50.8%. This was in a sample group in which there was almost equal distribution of dogs and bitches.

The other forms of cancer listed as causes of death were, in decreasing order of incidence: 31 lymphosarcoma (15.7% of cancer deaths, 5.3% of all deaths); 28 cancers of unknown origin or whose diagnosis of origin were questionable or unsubstantiated (14.2% of cancer deaths, 4.8% of all deaths); 6 mammary cancers, 4 lung cancers, 2 stomach cancers and 1 each of skin, intestinal and uterine cancer.

The mean age at time of death for Irish Wolfhounds that died of all forms of cancer was 6.6 years, while the mean age at time of death of those that died of osteogenic sarcoma was 6.6 years.

Perhaps it is noteworthy that the two types of cancer found most frequently in the Irish Wolfhounds in this study are osteogenic sarcoma and lymphosarcoma, both of which are rare in human medicine.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease accounted for 88 deaths in this period or 15.1% of the total deaths. As stated earlier, I had originally planned to differentiate between the various forms of cardiovascular disease, but early in the data analysis it became obvious that this would be impossible. Recent research and technology in this field in the last five to seven years of the study put the diagnoses of the earlier deaths in question. In the early years of the study, congestive heart failure was given as the principal cause of heart disease, but around 1981 cardiomyopathy became the most prevalent form, or at least more cardiovascular disease was being called cardiomyopathy. It would be difficult to determine if attending veterinarians were seeing and diagnosing the same disease. Several veterinary cardiologists have stated to me that the congestive heart failure of the earlier years was a form of cardiomyopathy, and that, in fact, the vast majority of all heart disease is cardiomyopathy in one form or another. Categorizing the deaths from heart disease in the early parts of this study would have required drawing conclusions that I was not prepared to draw and I therefore chose not to classify the types of cardiovascular disease.

A significant number of respondents related that a specific dog "dropped dead suddenly, probably of a heart attack." Autopsies were done on many of these dogs that verified cardiac disease, but they were often not extensive enough or not accompanied by pathology review, such as inspection of valve and muscle tissue which would reveal the underlying, more specific problem. All of this prompted my decision not to further classify this category.

Of the 88 dogs that died of cardiovascular disease, 50 or 56.8% were dogs and 38 or 43.2% were bitches, which was another surprising figure. The youngest wolfhound to die of cardiovascular disease was .83 months old at the time of death, a male. The oldest was 12.5 months old, a female. The mean age at the time of death for all dogs that died of cardiovascular disease was 7.3 years; mean age at death for dogs was 7.2 years and 7.5 years for bitches.

Gastric Dilitation Volvulus

The third most prevalent cause of death in Irish Wolfhounds in this study was gastric dilitation volvulus (gastric torsion) with 68 reported deaths, evenly divided between dogs and bitches. This is 11.7% of the total number of deaths and is a much smaller percentage of deaths than most owners and experienced veterinarians would probably have estimated. The youngest wolfhound to die of gastric torsion, a dog, was 1.08 years; the oldest, a bitch, was 11 years.

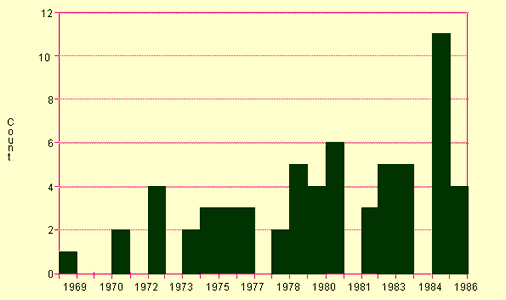

A question worth asking would be why there was such a dramatic increase in deaths from gastric torsion in 1984, but the sample is probably too small to be meaningful (see Table 3).

Table 3

Forty-eight wolfhounds died of unknown or undetermined causes. Autopsies and extensive pathology work-ups were done on many of these dogs with no conclusive diagnosis, but most were dogs that died suddenly or were simply found dead and the owners did not choose to have autopsies performed.

Arthritis

Thirty dogs in the study had to be euthanized because of arthritis, either as a result of a previous accident (5) or, most often, because of old age (25). A notably large number of respondents expressed deep regret at having to destroy an otherwise healthy animal because it could no longer rise or stand on its own. The average age at time of euthanasia of these wolfhounds (12 dogs and 18 bitches) was 9.3 years. The youngest of the group was only 4.6 years when euthanized, but its arthritis was a result of an earlier injury. The oldest was 12 years, but there were many six and seven year olds that were euthanized because of age-related arthritis. The bitches fared better in this category, with a mean age at time of death of 9.9 years, compared to the dogs, who had a mean age of 8.4.

Without discussing in depth the remaining, less prevalent causes of death, I would nevertheless like to comment on a few of the more striking findings. Since the period of this study included those years in which canine parvoviral enteritis (parvo) caused such a panic in the dog world, peaking around 1979-1982, I expected it to be a frequently listed cause of death. In fact, only two dogs in the study died of parvovirus, and the disease's appearance (or more frequent diagnosis) late in the study period would not explain the low numbers. The probable explanation is that the disease struck and caused most fatalities in very young dogs, and those under six months would not have been eligible for inclusion in this study.

Five deaths were listed as caused by disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, a rare and complex bleeding disorder caused by post-surgical infection. Medical researchers and veterinarians whom I consulted agreed that these five cases were questionable for two reasons:

- The post-mortem studies were sometimes not sufficiently complete to verify diagnosis.

- Its incidence is vastly out of proportion to clinical data from other sources.

The discovery of these five cases in this study was interesting from this standpoint alone.

I was prompted to undertake this study partly because I had been frequently told that the only statistics available on cause of death, gathered by a data-retrieval service from veterinary teaching hospitals and large emergency clinics throughout the country, list the major cause of death in Irish Wolfhounds as trauma. I felt then that those statistics are skewed by the fact that only particular types of cases and medical problems are presented to veterinary schools and emergency clinics. This study would seem to support my theory, since 21 wolfhounds died as a result of trauma, representing only 3.6% of the total deaths. The majority of these dogs' deaths were listed only as "trauma," but of those listed more specifically, five were killed by automobile and one by gun shot. As a result of, or in spite of most wolfhound owners' fear of general anesthesia and their wish to avoid it except when absolutely necessary, only five dogs died of anesthesia related problems. Six dogs were euthanized because of severe behavioral problems.

Summary

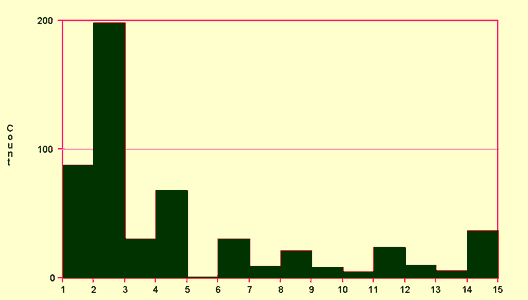

In summary, in this study of 582 Irish Wolfhounds (291 males, 274 females) in the United States that died between January 1, 1966, and January 1, 1986, the mean age at time of death for all dogs was 6.47 years (6.0 years for males, 6.55 years for females). The leading cause of death was cancer, with osteogenic sarcoma being the principal type of cancer. The causes of death, the incidence of each and the percentage of the total number of dogs in this study are:

- Cardiovascular Disease (88 or 15.1%)

- Cancer (197 or 33.9%)

- Arthritis (30 or 5.2%)

- Gastric Dilitation Volvulus (68 or 11.7%)

- Poisoning (1 or .17%)

- Bacterial Infection (30 or 5.2%)

- Viral Disease (9 or 1.6%)

- Trauma (21 or 3.6%)

- Intestinal Blockage (8 or 1.4%)

- Post-Surgical Complications (5 or .86%)

- Kidney Disease (24 or 4.1%)

- Liver Disease (10 or 1.7%)

- Euthanized Due to Poor Temperament (6 or 1.0%)

- Deaths from Various Other Causes (37 or 6.4%)

- Deaths from Unknown Causes (48 or 8.3%)

Table 4 - Cause of Death

References

- International Classification of Causes of Death and Manual of Joint Causes of Death. Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Print Office.

- E.P. Joslin and H.L. Lombard: "Diabetes Epidemiology from Death Records." New England Journal of Medicine (214:7, 1936).

- H.L. Lombard and E.P. Joslin: "Underlying Causes of Death of 1000 Patients with Diabetes." New England Journal of Medicine (259:924, 1958).

- M.A. Heasman and L. Lipworth: "Accuracy of Certification of Cause of Death." Studies on Medical and Population Subjects (#20, 1966).

- W.W. Holland, B. Sc., M.D.: Data Handling in Epidemiology. Oxford University Press, London, 1970.

*General Reference Source-Snedecor and Cochran: Statistical Methods (Seventh Edition). Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1980.

The following persons assisted with this study and that assistance is deeply appreciated: William Armon, D.V.M., Fenton Animal Hospital, Fenton, MO; Dr. Allen W. Hahn, Dalton Research Center at the University of Missouri School of Veterinary Medicine, Columbia, MO; Sheila McGilligan, Jewish Hospital, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

© Gretchen Bernardi, 1988. All rights reserved.

An Addendum

There are some personal observations worth noting that, while not relevant to the actual scientific data presented herein, are nevertheless enlightening and without which we could not derive a clear picture of these Irish Wolfhounds and of the breed in general in the United States. A few respondents, former owners, commented strongly that, while they loved the breed and enjoyed the time that they had spent with them, they would never again own one, because the sorrow involved in losing these dogs very young, time after time, was too great. But many more people took the time to write that they would continue to live with these dogs despite their short lives. It is surely a testament to the great appeal of this breed that so many people continue to own them through what is often great adversity.

I was heartened by the gratitude often expressed that this study had been undertaken, but far too many people expressed the hope that somehow Irish Wolfhounds would be guaranteed a longer life span as a result of these findings. This is not at all realistic. If we remove the dogs from this study that died of cancer, the mean age at time of death would be 6.4 years; if we removed the dogs that died of cardiovascular disease, the mean age would be 6.3 years; if we removed the dogs that died of gastric torsion, the mean age would be 6.3 years. In fact, if we removed the dogs who had died of cancer, cardiovascular disease and gastric torsion, the mean age at time of death would be 6.1 years.

From a statistical viewpoint, it would be erroneous to draw any real conclusions from this "trick" data, but the figures would seem to dispel any hope that we could, by simply eliminating a certain disease or problem, lengthen the life span of this breed. They would further seem to indicate that the problem lies much deeper and is more complex than mere susceptibility to specific illness.

This page was last updated 08/04/2021.